I teach yoga but don’t know Sanskrit.

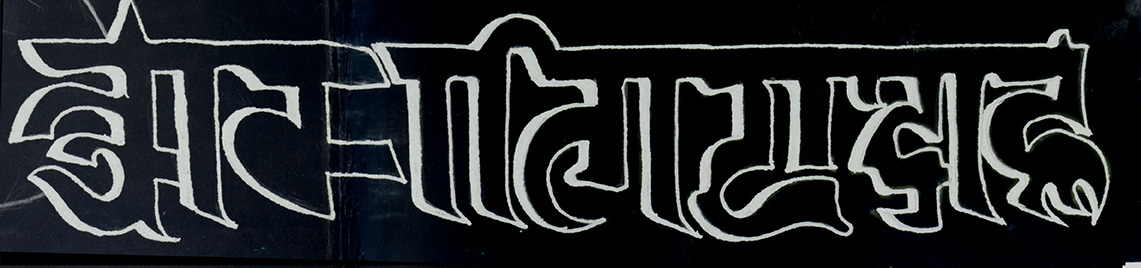

I’ve been able to pick up words from translations and studying yogic philosophy, from listening to the Sanskrit channel and from having read thousands of books and articles on yoga. I like the way the language sounds and the way it is composed. I like the way it looks when written out in its native form. I like the impressions it leaves in my body when spoken or chanted.

Sanskrit is considered the oldest language in the world, yet it stopped being developed as far back as 600 B.C. It is what most of the classical Hindu texts such as the Rigveda, Mahabharata, and Puranas were written in. It also forms the basis of many modern languages including Russian, German and English.

The word Sanskrit comes from sam (together, good, well, perfected) and krita (made, formed, work). It is said to describe works that have been well prepared, polished, perfected and made sacred.

According to the linguist Shalom Biderman via Wikipedia:

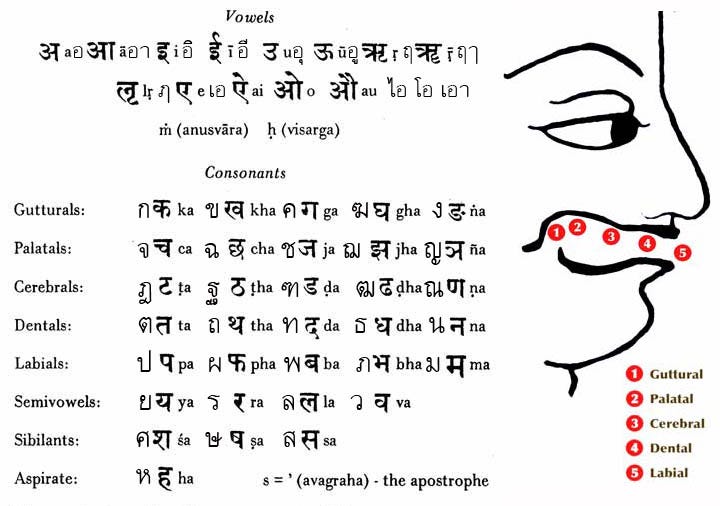

The perfection contextually being referred to in the etymological origins of the word is its tonal—rather than semantic—qualities. Sound and oral transmission were highly valued qualities in ancient India, and its sages refined the alphabet, the structure of words and its exacting grammar into a "collection of sounds, a kind of sublime musical mold.”

This speaks to the significance of chanting in yoga practice, as Sanskrit undoubtedly came into existence with this functionality in mind.

Another quote here, this one from the Irish historian William Cook Taylor:

It was an astonishing discovery that Hindustan (India) possessed in spite of the changes of the realm and changes of time, a language of unrivaled richness and variety, the parent of all those dialects that Europe has finally called “classical,” the source alike of Greek flexibility and Roman strength.

And another from Sir William Jones, an eminent scholar and philologist from 1786:

The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure, more perfect than Greek, more copious than Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar.

I once read a translation of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras by Rajneesh where he too spoke of Sanskrit in terms of this perfection. He described it as the ultimate language, void of dualistic assumptions and assertions. This idea of going beyond dualistic assumption is Sanskrit’s most significant contribution to the yogic sciences, and while its usage may seem to play a greater role in the scholarly (jnana) or devotional (bhakti) yogas, it can be just as well integrated into the more familiar asana classes that have come to represent yoga in the West. English by contrast has dualism built into nearly aspects— Yes/no, up/down, left/right, good/bad, is/isn’t, on/off, Lowes/ Home Depot. As to how this transcendent quality escaped Sanskrit’s gradual formation into English I have yet to know, but in the broadest sense language is a tool for thought, so it’s no coincidence that these dualistic conceptualizations cement our tendency towards ideology in the Western view of reality. We’re limited by our language to the extent we identify with it.

The quality most unique to Sanskrit is that it imparts the transcendence of duality, which is both remarkable and essential as a consistent yoga practice will expand one’s consciousness into greater recognition of the non-dual (advaita), or what in spiral dynamics is called a multi-perspectival view of reality. This puts us higher up on the cosmic ladder so we can look down over the sprawling interplay of opposing forces that keeps the phenomenal world (prakriti) in motion, yet without the need to align ourselves around one ideological bent or the other in our drive to understand it. While incredibly profound, this is quite a challenging perspective to maintain as non-duality demands a dismantling of our most deeply rooted assumptions, many of which are bound by the limitations of our language and the cultural perspectives supported therein.

When yoga entered the Western milieu it followed an inevitable trajectory towards corruption, Sanskrit being one of its first casualties. I’ve heard some yoga teachers say with an assured confidence that Sanskrit is not important— the names of the asanas don’t matter, chanting mantras is archaic, namaste may offend religious people, etc. If these naysayers were to support an argument for moving beyond the semantic conceptualizations inherent to language then I would be more receptive to this dismissiveness, but the more discerning part of me can’t help but see their widespread disinterest in Sanskrit comes from a lack of understanding as to just how profoundly yoga can transform an individual. Much of this is culturally bound and extends to fear around losing students, fear of being perceived as weird, and fear of their own ignorance around the subject as their practices lack depth, svadhaya (self-study) and most telling— a lack of curiosity.

Contrast this with another advanced Iyengar teacher I heard actually discourage the use of Sanskrit in class, this time under a guise of caution— and to maintain a certain humility, as if to insinuate Sanskrit holds such sacred meaning that it would be disingenuous— even reckless— for the uninitiated to use these words lest they carry a spell under which a teacher could convince students they know more than they actually do. This is a far less common take but may have some merit to more serious students. It at least acknowledges the power of Sanskrit and brings its use into consideration.

Every now and again I read of activists from India condemning Westerners for teaching yoga, claiming it is not theirs to teach-- Citing cultural appropriation to which presumably their own are not receiving the proper recognition on the world stage, or the proper monetary compensation most likely. And then unsurprisingly the flip side is also true-- Voices from this same cohort turn around and claim that Western teachers are erasing the Indian identity from yoga by not using Sanskrit, citing a cultural chauvinism that co-opts only the physical aspects of the practice to entice the Lululemon Starbucks Red Bull crowd. I actually agree more with this take, but would say it results not from any coordinated attempt to erase Indian culture per se, but more so from what I described above— ignorance, laziness and complacency— tamasic qualities about as far removed from yoga as I can possibly think of.

Regardless of where you are in your journey, Sanskrit is definitely worth a deeper look. It has the power to transform an individual in and of itself, so its coupling with asana and other yogic techniques should not be so mindlessly brushed aside.

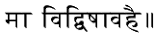

Ma vid visha vahai

Let us be together, strong and energetic

Namaskaram to you all.